My Latest Book in English on Amazon

24 de February, 2025

A Practical Guide to AI for Product Managers

11 de March, 2025After a series of new articles, I will resume publishing the chapters of my latest book, “Digital Transformation and Product Culture.” This time, the chapter is about team structure, a critical subject for the success of any product.

The product development team is responsible for executing the strategy and achieving the objectives to reach the product vision. Therefore, an essential part of defining a strategy is designing and implementing the team structure. To do this, it is important to understand the different ways to organize a product development team and determine which is most suitable for your strategy.

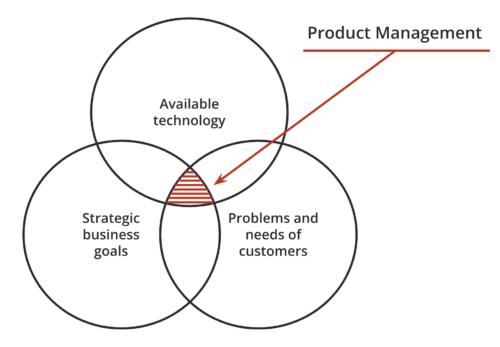

Recalling what we discussed in the chapter on the so-called digital transformation:

Digital product management

It is the function responsible for connecting the company’s strategy with the problems and needs of customers through digital technologies. This function must, at the same time, help the company achieve its strategic objectives, while solving problems and meeting needs of customers.

Basic structure

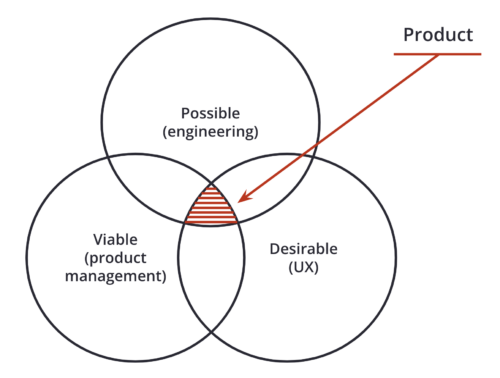

This image gives us a good indication of what the basic structure of a product development team is:

We need people from engineering, product design, and product management. The minimum team consists of two engineering professionals, one product designer, and one product manager. The ultra-minimum team consists of only two individuals: one from engineering and the other with a business and design-oriented profile. This ultra-minimum team can function in the beginning, but if the product is well-received, this team will quickly need to expand.

What is the best ratio between engineering, UX and PM?

Throughout my career, both in companies where I led product development teams and in my work as a consultant, I have con- sistently found, with few exceptions, a ratio ranging from 5 to 9 engineers per product manager (PM). When it comes to designers, the most common ratio is 1:1 with PMs for user-focused product teams. Therefore, my general recommendation is to have 5 to 9 engineering professionals per PM and 1 UX designer per PM. Here, when tallying the engineering professionals, we should also take into account the individuals from the structural teams that we will discuss later.

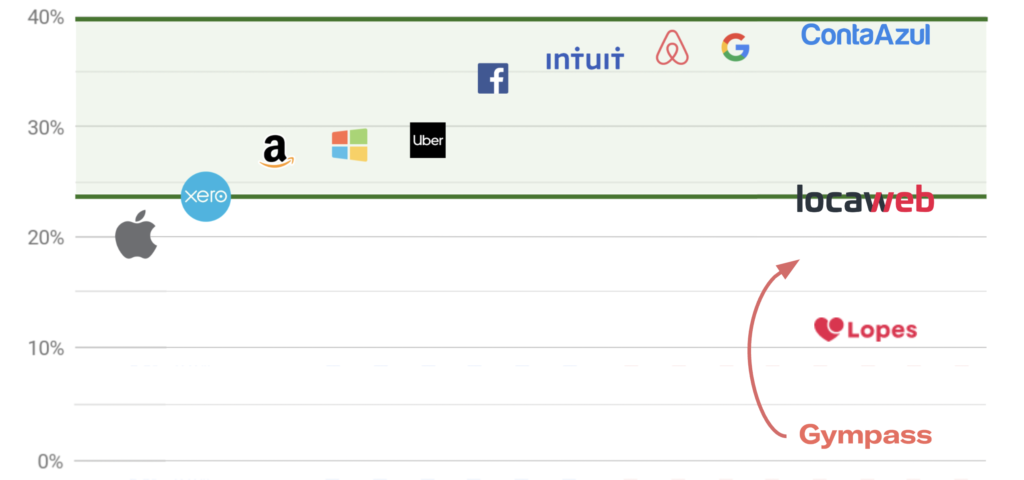

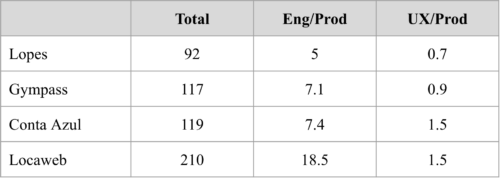

Here are some figures and team ratios from the product development teams of some companies where I have worked:

At Lopes, we operated at the lower end of the recommended ratios, while at Gympass, the proportions were more in line with the recommendations. In the case of Conta Azul, the ratio of engineering to product professionals fell within the recommended range, but the UX/PM ratio was 50% higher than the recommended value. This was attributed to Conta Azul’s strong emphasis on providing a compelling user experience, which was one of the company’s core values, emphasizing the delivery of a “WOW experience.”

Conversely, at Locaweb, we observe that the ratio of engineering to product professionals exceeded double the upper recommended limit. This was influenced by the technical nature of Locaweb’s products, such as Web Hosting, Email, Cloud Server, SMTP, Email Marketing, and E-commerce platforms. However, this large proportion of engineering professionals relative to product professionals resulted in a 50% higher UX-to-product professional ratio. This adjustment was necessary to enable UX professionals to support product professionals in discovering and defining the actions needed to achieve the desired outcomes.

How big is the product development team in relation to the company as a whole?

When I joined Gympass in 2018, the company already had 800 em- ployees, but the product development team, consisting of product managers, designers, engineers, and data professionals, comprised only 30 individuals, which was less than 4% of the company, a seemingly low figure.

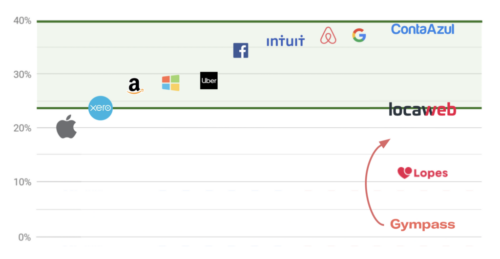

Shortly after joining the company, I had to present my plan to the board to expand this team. I decided to include a slide with a benchmark of some well-known technology companies.

I used LinkedIn to obtain some estimates of the size of the product development teams of these companies compared to the total number of employees. Most of them have between 24% to 40% of their workforce in the product development team. The exception is Apple, with 20%, but it’s important to consider that they own all their physical stores, so all the salespeople in these stores are also their employees. Conta Azul, Locaweb, and Lopes are from my past experiences. Lopes, a traditional real estate company undergoing digital transformation, had about 11% of its workforce in product development. At Gympass, we were able to increase from 4% in mid-2018 to 18% by the end of 2019.

However, we cannot define the ideal team size solely through benchmarking. We need to consider other factors within the company: what needs to be done and where to invest.

What to do

From the company’s objectives and understanding of user problems, we create our product vision and strategy. Having this clarity helps us define what we need to do to execute this strategy, the results and objectives we want to achieve, and the team required to implement this strategy.

For example, at Gympass, we developed products for gyms, our clients’ HR departments and their employees. We decided to have dedicated teams for each of these participants in our marketplace. Additionally, we needed tools to manage payments received from HRs and employees and those we had to make to the gyms, so we also had a team focused on that. These were what we call product teams, generating results for Gympass, such as more users and less manual operational work.

In addition to product teams, we also had structural teams to handle themes such as SRE (Site Reliability Engineering), tools common to all product teams, data, and security, as I will explain shortly.

These product and structural teams had their own visions and strategies aligned with the global vision and strategy, and based on that, they proposed their own team structures. For example, at Gympass, the team focused on our clients’ employees decided to split into two teams: one focused on growth, helping employees know that the company offers Gympass, encouraging employees to download the app, create an account, and subscribe to the service; the other focused on digital experience, meaning helping employees make the most out of Gympass, finding and using suitable gyms, activities, and wellness apps. What to do is one of the drivers to define the structure and size of the team.

How much to invest

On the other hand, we need to determine how much we are willing to invest in this team. Assembling a product development team costs money. Suppose that, based on what we have defined we want to do, we create a product development team structure that requires 15 people. Let’s consider $6,000 as the average monthly salary for your team members. ncluding all taxes, benefits, and vacation costs, this would amount to $9,600 per month. So, the total monthly cost of this team is $144,000 or $1,728,000 per year. It’s a significant amount.

The purpose of this team is to bring results to the company, but sometimes results may take time to be generated. In all the new products we build and launch, until we launch them and start generating some revenue, this team will only incur costs. Do we have the financial resources to invest every month to pay the salaries and labor charges of this team while it is not generating results? Please note that here I am only considering salaries, without bonuses and stock options.

Therefore, we need to know how much we can invest and what we need to do to be able to define the ideal size of our product development team.

In the following article, we will see how to organize product teams. Stay tuned!

Digital transformation and product culture

This article is another excerpt from my newest book “Digital transformation and product culture: How to put technology at the center of your company’s strategy“, which I will also make available here on the blog. So far, I have already published here:

- About the book

- Part 1: Concepts

- Chapter 1: The so-called digital transformation – Project and Product

- Chapter 2: Uncertainty and digital transformation

- Chapter 3: Types of company

- Chapter 4: Type of company vs digital maturity

- Chapter 5: Business models

- Chapter 6: Agile, digital and product culture

- Part 2: Principles

- Chapter 7: Deliver early and often – Measuring and managing the productivity – Case study: Dasa Group – Case study: Itaú Unibanco

- Chapter 8: Focus on the problem – O Famoso Discovery de Produto – Why the “business demands => IT implements” model does not work – Case study: Magazine Luiza

- Chapter 9: Result delivery – Outsource or internal team? – Case study: Centauro

- Chapter 10: Ecosystem mindset

- Part 3: Tools

- Chapter 11: Product Vision – Product vision examples

- Chapter 12: Product Strategy

- Chapter 13: Team Structure

Workshops, coaching, and advisory services

I’ve been helping companies and their leaders (CPOs, heads of product, CTOs, CEOs, tech founders, and heads of digital transformation) bridge the gap between business and technology through workshops, coaching, and advisory services on product management and digital transformation.

Digital Product Management Books

Do you work with digital products? Do you want to know more about managing a digital product to increase its chances of success, solve its user’s problems, and achieve the company objectives? Check out my Digital Product Management books, where I share what I learned during my 30+ years of experience in creating and managing digital products:

- Digital transformation and product culture: How to put technology at the center of your company’s strategy

- Leading Product Development: The art and science of managing product teams

- Product Management: How to increase the chances of success of your digital product

- Startup Guide: How startups and established companies can create profitable digital products