Product Owner Misconception #1: Is It Just a Product Management Career Step?

7 de January, 2025

Product Owner Misconception #3: Do they focus on execution while product managers focus on strategy?

20 de January, 2025This is the second article in a 3 part series about common misconceptions of the usage of the term “Product Owner” in the broader product management context.

In the first article, I discussed the misconception of considering “Product Owner” as a step in the Product Management career ladder.

Now, let’s talk about the 2nd misconception:

Misconception #2: Do product managers manage product owners?

When I joined Lopes, a Brazilian real estate company, to lead its digital transformation and started getting to know the team, I noticed we had Product Owners in each product development team. These teams also had engineers and a product designer. A few Product Managers led the Product Owners. That’s a common scenario I frequently encounter in my consulting clients.

This happens mainly because of 2 reasons.

Reason 1: the misinterpretation of the word manager. This issue often arises in organizations transitioning from more traditional hierarchical structures. In such setups, titles like ‘manager’ are commonly associated with direct people management responsibilities. As Agile and product-centric practices take hold, these legacy interpretations can impose some limitations on our organizational structure.

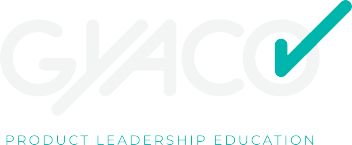

The “Product Manager” title has the word “manager” in it, so this person must manage other people, right? Wrong! In the same way a project manager manages projects, not people, and an account manager manages accounts, not people, a product manager manages products, not people. So we shouldn’t give people management responsibilities to a Product Manager. If we decide to give people management responsibilities to a product manager, we should give them a new role. The most common is Group Product Manager (GPM). Still, I have also seen Product Lead, Head of Product, and Product Director as alternative names for the role of managing product managers.

So, in a team with engineers and a product designer, we should have a “Product Manager” who may adopt “Product Owner” best practices if the team uses Scrum or a similar as its guiding framework for managing work.

Reason 2: average salaries of PO, PM, and GPMs. This reason is a hard truth: the average salaries of POs are lower than the average salaries of PMs, which, in turn, are lower than the average salaries of GPMs. So, to lower costs, executives may use the PM leading POs instead of the GPM leading PMs organogram.

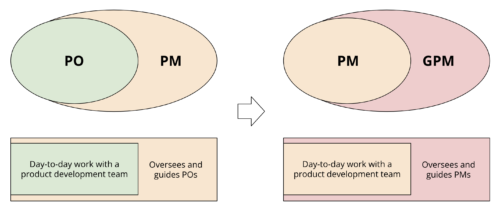

| Average Annual Salary (k USD) | US | Germany | Netherlands | Brazil |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Owner | 110 | 85 | 85 | 18 |

| Product Manager | 126 | 105 | 110 | 35 |

| Group Product Manager | 195 | 115 | 122 | 50 |

| Sources | Product School | TechPays | TechPays | PM3 |

Average Annual Salaries in thousands of USD

While cost-saving measures like assigning Product Managers to manage Product Owners might seem logical, they can create unintended consequences. For instance, this structure may demotivate team members by misaligning their responsibilities with their titles and pay. Over time, it could also hinder the organization’s ability to attract and retain top-tier talent, especially in competitive markets where clear role progression is highly valued. Imagine your top Product Owners realizing their work is better compensated at companies that use the Product Manager title. Or your best Product Managers discovering that their responsibilities—managing product people—are compensated at the GPM level elsewhere.

Solution: To fix this misconception, we should use the GPM leading PMs organogram:

This may cost more, but it opens up the opportunity to bring more senior people to the team and ask for improved engagement and impact from existing team members. The salary increase doesn’t need to be given at once; it may be given based on each person’s demonstrated evolution according to the mission of the product management role: solving customer problems with technology in a way that generates results for the company.

This adjustment aligns with the broader objective of rethinking the Product Owner role in modern product management that I’m discussing in this series of articles. Moving away from outdated or cost-driven structures not only clarifies responsibilities but also reinforces the strategic value of the product management practice as a whole.

It’s important to note that titles and structures vary widely across organizations. While this recommendation aligns with many modern product management practices, some companies may use alternative naming conventions or hybrid frameworks. Regardless of terminology, the core principle remains the same: aligning roles with responsibilities to ensure clarity, foster collaboration, and drive better outcomes.

Conclusion

So there you have it: the 2nd misconception, thinking that a PM manages POs, why this misconception came to be, and how to avoid it.

In conclusion, the misconception that Product Managers should manage Product Owners stems from semantic misunderstandings and cost considerations. By adopting a structure where group product managers lead product managers, organizations can foster a clearer hierarchy, improve team morale, and ultimately enhance their product management capabilities. This approach not only resolves the immediate challenges but also sets the foundation for a more effective and scalable product management practice.

In the following and last article of this series, I’ll discuss the third misconception: Do product owners focus on execution while product managers focus on strategy?

Stay tuned!

Workshops, coaching, and advisory services

I’ve been helping companies and their leaders (CPOs, heads of product, CTOs, CEOs, tech founders, and heads of digital transformation) bridge the gap between business and technology through workshops, coaching, and advisory services on product management and digital transformation.

Digital Product Management Books

Do you work with digital products? Do you want to know more about managing a digital product to increase its chances of success, solve its user’s problems, and achieve the company objectives? Check out my Digital Product Management books, where I share what I learned during my 30+ years of experience in creating and managing digital products:

- Digital transformation and product culture: How to put technology at the center of your company’s strategy

- Leading Product Development: The art and science of managing product teams

- Product Management: How to increase the chances of success of your digital product

- Startup Guide: How startups and established companies can create profitable digital products