Leading and lagging indicators

22 de November, 2021Innovation: the job to be done

6 de December, 2021The first step to creating a new software product is to understand the problem. It is very tempting, as you begin to understand the problem, to go on and seek solutions. Human nature is to solve problems.

Every software developer has some story to tell about demands that goes like this: “So, I need a system that does this and that, I need to have a field so I can type this information and it should give me a report that shows this.” Then, when the system is delivered, the person says “Well, this helps me, but now I also need a field to insert these other data and I need the system to export a file .txt with commas and that end of line marker.” In other words, demands come in the shape of solutions and normally don’t even mention the problem to be solved.

Next, I’ll share some techniques to focus on the problem.

Interview

It is a good way of understanding clients, the problems they have, the context in which these problems happen, and what motivates their solution. However, it is necessary to be careful, because the respondent will try to hand out the solution of what is thought to be the problem. You must be careful not to belittle the suggestion but should always keep the conversation focused on the problem.

The interview in which you talk directly to your client is considered a qualitative method, that is, you ask a few questions but get the opportunity to deepen the answers.

Next, there is a set of questions that will help to keep the conversation focused on the problem:

- Tell me more about your problem.

- What is the greatest difficulty you have regarding this problem?

- What motivates you to wanting this problem solved?

- Where does this problem usually happen?

- When did it happen for the last time? What happened?

- Why was it difficult/complicated/bad?

- Did you manage to find a solution? Which one(s)?

- What didn’t you like about the solutions you found?

For instance, let’s go back to the subject of the car and the cart of Henry Ford. Now imagine a dialogue between Henry Ford and a hypothetical Mr. Smith, a possible buyer for Ford’s product at that timeframe:

Ford: Mr. Smith, what distresses you the most?

Smith: Mr. Ford, the most distressful thing for me is that I don’t spend too much time with my family.

Ford: And why is that?

Smith: Because I spend too much time in the cart going from one place to another. If I could put one more horse to pull my cart it would go faster and I could spend more time with my family.

Ford: Oh, I see your problem, and I have an even better solution for you — it’s called car.

Do you think that Henry Ford got the problem? Or that he understood the solution Mr. Smith presented to him and developed a solution based on that suggestion? Do you think the real problem of Mr. Smith was that he didn’t spend too much time with his family?

Let’s try using the same questions shown previously to see if we can get the problem:

Ford: Mr. Smith, what distresses you the most?

Smith: Mr. Ford, the most distressful thing for me is that I don’t spend too much time with my family.

Ford: And what is the greatest difficulty you have regarding this problem?

Smith: I spend too much time at work, and going from one place to another, without talking to people.

Ford: What motivates you to wanting this problem solved?

Smith: I have small children and, because of work, I spend too much time out of home. When I get home, my kids are already asleep.

Ford: Where does this problem usually happen?

Smith: At work.

Ford: When did it happen for the last time? What happened?

Smith: Practically every day. It happened yesterday. I think I manage to get home in time to see my kids still awake once a week…

Ford: Why was it difficult/complicated/bad?

Smith: Because it has taken me away from the kids.

Ford: Did you manage to find a solution? Which one(s)?

Smith: I got off from work earlier.

Ford: What didn’t you like about the solutions you found?

Smith: The work piled up on the other days.

Note that this conversation can generate a solution such as the invention of the car to help Mr. Smith to get home faster. However, it could also be the motivation for creating a more efficient work process or a machine that would do the work for Mr. Smith.

You might have a solution in mind. But consider having a real interview, focusing on the questions for really understanding the client’s problem.

Survey

Another way of obtaining information from clients is through surveys. This method is considered quantitative because it seeks to survey a considerable amount of people in order to get what is known to be of statistical relevance. That is, for being confident that the results obtained weren’t got by chance.

For example, in case you ask in a survey if a person has iPhone or Android, and only get two people to answer, that is, only two answers — being both iPhone, both Android or one iPhone and the other Android — it is very difficult to reach a conclusion. But, if you have many more answers, you have bigger chances to picture the real world in your survey.

There are great tools for online surveys, such as Google Form and Survey Monkey. There is also a Brazilian tool called OpinionBox that, besides building your questionnaire and collecting the answers, allows you to select people for responding it based on the profile criteria you specify.

Surveys don’t have to be necessarily taken online. You can also perform them by phone or live. There are companies that can help you collect the answers.

Deciding to do a survey is easy, but building the questionnaire is hard. The first step is to have your survey goal very clear. Then, create your questions with these two main rules in mind:

- Be brief. The shorter your survey, the bigger are the chances of getting a good number of answers and guaranteeing a high statistical relevance.

- Be clear. Especially in online surveys, when you are not interacting with the respondent, there are big chances of the person misinterpreting your question. One good way of testing your questionnaire is to test it live with some people. Check if they understand each question, or if they have some difficulties in comprehending some part of it.

Check some examples of bad questions that could bring up some misguided interpretations or mix up the quality of the answers, and suggestions of how these questions can be improved:

- Original question: How short was Napoleon?

- Improved version: What was Napoleon’s height?

- Original question: Should concerned parents use compulsory child seats in the car?

- Improved version: Do you think the use of especial child seats in the car should be compulsory?

- Original question: Where do you like to drink beer?

- Improved version: Break into two questions: Do you like drinking beer? If yes, where?

- Original question: In your current job, what is your satisfaction level regarding salary and benefits?

- Improved version: Break into two questions: What is your satisfaction level with your salary in your current job? What is your satisfaction level with your benefits in your current job?

- Original question: Do you always have breakfast? Possible answers: Yes / No.

- Improved version: How many days a week do you have breakfast? Possible answers: Everyday / 5-6 days / 3-4 days / 1-2 days / I don’t have breakfast.

Observation

Another very useful technique to understand the problem is to observe. Seeing the client-facing the problem or having a need, in the context that it occurs, can be inspiring!

Observation is a qualitative way of understanding a problem. In order to make a good observation, be prepared; that is, hold in your hands a set of hypotheses. In each round of observation, re-evaluate your hypotheses and adjust them, if necessary. Usually, after 6 or 8 observations, you can already notice a pattern.

Observation may or may not have the observer’s interference. For example, if you are observing consumption habits in a drugstore, you can watch people without them noticing you. But in a usability test, in which you invite people to test your software, people will know that you are observing them. The observations can be complemented with interviews, helping to improve the quality of the findings.

A very useful technique to find out problems in the use of the software is to observe what the user does 10 minutes before and 10 minutes after using it. For example, if the user catches information in some other system to insert into the software. Maybe here there’s an opportunity for you to catch information from the other system automatically. And if, after using it, the user pastes information to a spreadsheet for building a graphic, eventually your software could spare the user from this work and automatically build this graphic.

Observation usually is depicted as a qualitative method. But you can and should treat it as a quantitative observation. For such, observe the user and some important metrics such as statistics of access and use, engagement, NPS, revenue, new clients, churn, etc. In other words, it is a way of observing the users’ behavior while they engage with your software.

Problem mindset vs solution mindset

When we hurry to launch an MVP, we are creating a solution for a problem. However, a very important step to creating a good solution is the understanding of the problem.

It is human nature to jump into solution mode when we learn about a problem. When we hear about a problem, we immediately start thinking about solutions. However, the more time we spend learning about the problem, the easier it will be to find a solution and good chances are that this solution will be simpler and faster to implement than the first solution we think about.

Here’s a great Albert Einstein quote:

“If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.”

Einstein believed the quality of the solution you generate is in direct proportion to your ability to identify and understand the problem you hope to solve.

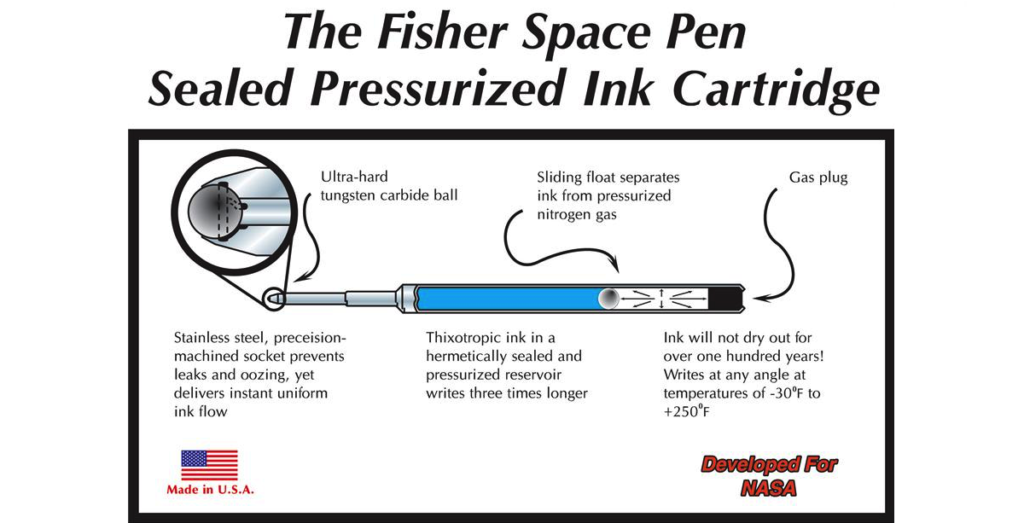

Let me tell you a short story to illustrate this. During the space race, scientists were faced with the issue of writing in space where there’s no gravity to make the ink go down in a ballpoint pen. Americans started their R&D efforts and after some time and a few million dollars, they built a pen with a small engine that pumps ink to the paper, even with no gravity. Meanwhile, Russians decided to use pencils, which can do the job of writing in no gravity environments.

That focus on solutions, without a good understanding of the problem and the motivation to have this problem solved, can be quite harmful. It can make us spend unnecessary time and money to get to sub-optimal solutions. This is a cultural issue, i.e., a behavior that we can and must change. The first step to changing a behavior is recognizing it when it happens. When you, as a product manager or a product development team member, receive a request to implement something, ask the person who brought the request what is the problem that this “something” is supposed to solve and why there’s a need to solve that problem.

Here are some examples from the companies I worked for.

At Locaweb, a web hosting provider in Brazil, the hosting and email services may stop working due to external factors such as the domain associated with the hosting and email not being renewed.

- Original solution: Registro.br, the Brazilian registrar for .br domains released an API to allow Locaweb to charge the customer domain on behalf of Registro.br. At first, the idea seems good, since Locaweb billing the domain looks like the easiest way to guarantee that the customer knows that it has to pay for the domain registration to maintain the hosting and email services functioning properly. However, when we analyzed deeper, we saw that this solution could generate some problems. The customer would be billed twice for the same domain registration because the Registro.br would continue billing the domain. What happens if the customer pays both bills? And if she pays only Registro.br? And if she pays only Locaweb? In addition, implementing a new type of billing where we will bill for a third party service was something new to the Locaweb team. New processes would have to be carefully designed.

- Actual solution: we started to wonder if there would be simpler ways to solve the problem of helping our customer not to forget that he has to pay for her domain registration at Registro.br. Since it would be possible to charge for Registro.br services, it was possible to access the information about the about-to-expire domain. We decided to design a simpler solution: we will implement a communication sequence with this customer advising him of the importance of paying Registro.br to ensure that the email and hosting services continue to operate normally. This is a much simpler solution than implementing a double billing process. If Registro.br provides us with the billing URL, we can send this link information to the customer and the chances of solving the problem will increase even further. And a communication sequence is much simpler and faster to implement than a duplicate billing process.

At Conta Azul, a SaaS ERP for MSE (micro and small enterprises) we used accountants as one of our distribution channels and wanted to increase sales through accountants.

- Original solution: batch purchases, where accountants would acquire a fixed number of Conta Azul licenses to resell to their customers. A system to manage batch purchases would take around 3 months to be implemented since it should allow accountants to buy Conta Azul licenses in bulk, but should only start billing the accountant’s customer when she actually activated the license.

- Actual solution: accountants didn’t care about batch purchases. What they wanted was to provide a discount to their customers so they could subscribe to Conta Azul with this exclusive discount provided by their accounts. The cost to implement this was zero since the system already had a discount management feature.

At Gympass, a fitness partner who was joining our fitness network requested us to present their waiver to everyone who check-in in their facilities.

- Original solution: change our app to ask end-users who go to this fitness partner to read their waiver in our app and to check a box stating they read and are ok with it.

- Actual solution: no change to our app. Use a customizable text field in the gym set up in our system that is normally presented to users who will check-in in that gym to present the following text: “By checking in, you agree with the waiver located at http://fitnesspartner.com/waiver”.

Don’t get me wrong, it is really good that everyone brings solutions to the table whenever we want to discuss something to be done by the product development team. The more solution ideas we have, the better. However, we need to educate ourselves to have a deeper understanding of the problem behind that solution, so we have a chance to find simpler and faster to implement solutions. And it is ultimately the product manager and all product development team members’ job to ask what is the problem and why we need this problem solved.

Concluding

In concluding this chapter, I’ll make some final considerations on this stage of understanding the problem that is crucial for your software product’s success.

I put aside, on purpose, a technique called focus group, in which we gather a group of people (between 6 and 15 individuals) to discuss a certain problem. It is a technique considered qualitative as it enables to deepen in the questions that are being discussed.

The reason I put it aside is that, in these discussion groups, there’s a strong social influencer element in which more assertive and extrovert people tend to dominate the discussion and end up polarizing the group’s opinion. In my point of view, individual interviews are generally much more relevant, unless in situations when the goal is to research exactly the influence and social interaction of the group.

Another important point to consider during your discovery of the problem is who are the people having this problem and which characteristics they have in common. Besides understanding very well the problem, it is important to know for whom we are intending to solve it and what are their motivations and aspirations. It is important to keep this in mind during the process of discovering the problem.

You might be asking yourself “Why is so important to invest that much time and effort in understanding the problem?” The answer is simple: developing a software product is expensive. Investing in good comprehension of the problem, of the people who have them, of the context in which it occurs and the motivation people have to see it solved, is essential for not wasting time and money building the wrong solution.

Lastly, as I mentioned before, the methods are not exclusionary, they can and must be used together, for they are complementary. An observation is complemented with an interview. The findings in observation and interviews can be confirmed (or confronted) with the results of a survey or the analysis of collected metrics.

Digital Product Management Books

Do you work with digital products? Do you want to know more about how to manage a digital product to increase its chances of success, solve its user’s problems and achieve the company objectives? Check out my Digital Product Management bundle with my 3 books where I share what I learned during my 30+ years of experience in creating and managing digital products:

- Startup Guide: How startups and established companies can create profitable digital products

- Product Management: How to increase the chances of success of your digital product

- Leading Product Development: The art and science of managing product teams

You can also acquire the books individually, by clicking on their titles above.